Part 1 (of 2): “Quasi-Freedom”

by Jeff C.

QUASI-FREEDOM Day 1:

AFTER GIVING AWAY nearly all of my wonderful stuff, after anxiously paging through the only entertainment in my room (a borrowed art book), and after having my very last wasteful nap in prison, the cell doors racked in my now echo-y room on a tier in which I'd dwelled on since the ‘90s and within 15 minutes I was in a van uncuffed, unshackled, looking at shapes and sizes of cars I'd never seen before, staring at people texting while driving, and gawking at the sheer amount of summer skin on display.

The surrealness of this moment pressed down on the back of my eyes and, during the van-ride to Seattle, I knew I could let myself cry if I merely allowed it to happen.

In the van, seeing shades of green an RGB screen can't duplicate, seeing Mt. Rainier not on a license plate but floating lazily above the clouds, and having my ears pop for the first time since my last vehicle ride 14.5 years ago, I did, indeed, allow the tears to leak out, deftly wiping them away so the convicts in the van with me couldn’t see them; now, on the sidewalk, able to walk away as freely as a dog into traffic if I so desired to be that stupid, I wouldn't let anything interfere with the overwhelming influx of sights, sounds, and feelings—both emotional and physical—because, yes, I did, indeed, reach down and touch the earth. Somehow I refrained from kissing it.

QUASI-FREEDOM Day 3:

AFTER TWO DAYS of running down the stairs each time a garble name is blasted on the PA for [Muffle Garble] to report to the front desk and it mostly being for me, after unblinkingly staring out my bay window (my #$%@*^ Bay Window!) that overlooks Seattle's 8th Avenue and Cherry Street with a view of not only trees that go all the way to the ground and of all the amazing boat traffic in the Puget Sound but also I stared from my second floor windows at the people in summer clothes (or lack thereof), and after plotting my route out on an awesome wall map (which suddenly isn't illegal in this particular DOC facility) of downtown Seattle, the unlocked front door was pushed open by me to take in my first few hours in 255 months not under the ever-watchful eye of the Department of Corrections or their cameras. I had three mandatory stops (with no allowable “deviations” to other locations): 1.) the bank (irony heavily, surreally noted that it was my last stop before prison), 2.) the Department of Licensing (oy vei, I'll spare you the stressmare that was—all because the DOC apparently hadn't noticed that 5 months prior there'd been a price hike on people who hadn't had an ID in over 5 years so the check they'd given me wasn't enough), and, 3.) the Metro for my month bus pass.

![]() |

| Bishop Lewis Work Release |

But mostly I looked at all the tall buildings with a craned neck, glanced glimmeringly at the gadgets over people’s showers, and tried not to gawk at all the beautiful people all while trying not to seem like an alien and/or tourist who wanted (as I was later described to want to do) to lick all the shiny things. But my eyes weren't merely hungry—they'd been starved and hadn't known it until given that first taste and suddenly my eyes were ravenous (and quick to leak). I couldn't stop looking at all the new—it seemed—everything. It would take an hour to catalog all the things I'd never seen before. Yes, cable TV over the last 925 weeks allowed me to feel like I wasn't completely a stranger in a strange land, but TV is not reality. Despite what it loudly proclaims.

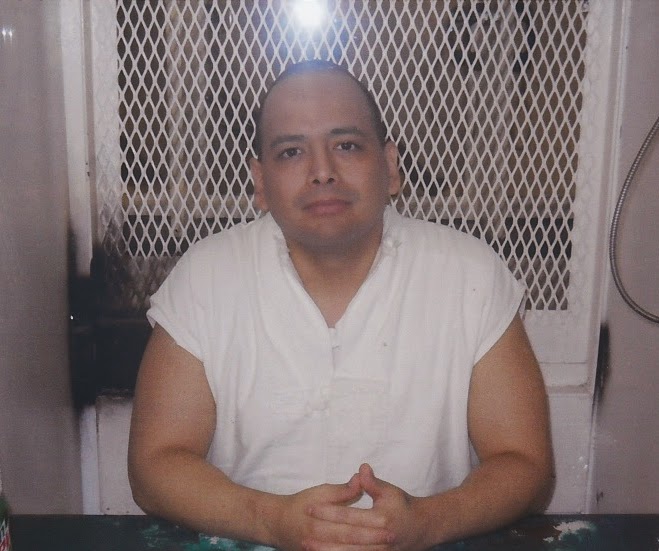

<Insert My Room at Bishop Lewis Work Release>

QUASI-FREEDOM Day 6:

MY EMOTIONS RANGED from the über-giddy to the grittingly stressful on my first day of job searches. Giddy because, especially in one of the most beautiful summer weeks of sunny weather in downtown Seattle, I was among the crowds. Just being able to walk amongst people was, at that time, almost too much—in that it was a combination of stimulation overload and I needed to not succumb to—what?—perhaps the self-pity induced by the complete waste I’d chosen my life to become. That slimy feeling always slithers underneath the surface—especially when faced with the majesty of crowds or whenever someone talks about what they’ve done/accomplished in the last nearly two decades. Shit, merely mention 401(k)s, mortgage payments, or any other adult, responsible thing to me and I either scramble to change the subject or defend myself with some lame feign at humor because I basically constantly feel like I am where I’d’ve been if fired, identity thieved, and had no insurance when all my stuff burned to ash in front of my eyes and it was all my own doing—essentially I feel I’m far behind where I ought to be in life and I don’t even get the American luxury of blaming someone else (and my only defense against this oppression is repression).

![]() |

| The Smaller Buildings of Seattle |

So going out and interacting with people who have no idea what I’ve done, where I’m from, how I’d fucked up my life, or how beautifully alien the lights, sounds, colors, and textures are to me—it’s all both fascinating and intimidating.

But the intimidation wasn’t just internal, it was external as well because I did have a job to do: finding a job. Bishop Lewis Work Release gives its residents (note: no longer “inmates”) 30 days to find a job or...well, go back to prison. Yet, they only allow its 68 residents to go but thrice a week to the Seattle WorkSource to use its services and something else quite important. I’d been fantasizing about and tantalized by glimpses over bosses’ shoulders and on television and in magazines and out of the mouths of the babies that come into prison in the last 15 years who grew up on and in it: the fabled, mythical, magical internet. The beholder of all information. The place I (and all who know me) knew, before I ever double-clicked once, that I’d become instantly addicted to. Hype, like hope, can be a dangerous thing, though. I never had to curse my way through dial-up speeds and blue screens of death (like polio and the Salem Witch Trials, these were only things I’d ever read about, not lived through, so I had no fear of them). But as a result of missing out on all that, I never instilled a (perhaps healthy) layer of calloused cynicism towards the internet. As if your only source of information about some exotic locale was slick, glossy travel brochures that intentionally never enlightened you about mosquitos, malaria, and airline meals—that’s what I knew about the internet: all the hype, none of the frustration. Oh, sure, I’d heard horror stories about malware and identity theft and iCovets being robbed at crochet needle point—but I’d assumed that they’d worked most of the kinks out of the internet when they’d upgraded to The Internet 2.0 and one could at least easily find out simple information at the speed of Google.

![]() |

| Seattle's Public Library |

What I hadn’t expected was such a plethora of counter-intuitive mis-design on so many websites. Sure, absolutely, many sites are fantastically user-friendly, but there are simply far too many that seem like they were never gone through—e.g. if a job is offered in Seattle from a company’s website and that is one of the multiple choice selections, then why isn’t there a Washington State selection or at the very least don’t block forward progress by saying, “All required fields must be filled in”—or is there a Seattle, Florida, that I’m not aware of?

Companies often hire outside efficiency experts because they have that outside perspective, so, if I may have the attention of all the content providers on the internet: Few have a better perspective on this than moi—design, check, then have someone else check if it actually works. Oh, yeah, then actually fix the damn problem. Let’s get this shit right, people. This isn’t just for me and my frustration level; it’s to make the world a better place.

![]() |

| Sunshiny Seattle |

I somehow signed up for my first email account (not always an easy thing to accomplish with zero internet skills and no phone number or other email address to be its backup; but thankfully my sister had created a different one for me that I used as the “source” one to send password changes to). I then...proceeded to be really rather annoyed that the televised hype that the various search engines turned out to be as they sputtered into my lap with an often overwhelming plethora of just plain useless and irrelevant supposed answers. Silly me, I’d been fooled into thinking I could type in a question and get something useful back. Not 634,981 results in 0.18 seconds—not a one which is helpful.

That afternoon I also filled out my first job application in an art supply store and quickly realized I needed to go back to that stammering internet and get those oh-so-important-to-an-employer essentials like my elementary school physical address.

![]() |

| Job Searching with Seattle's Freemont Troll |

On job searches I also quickly learned something else by entering businesses. When out on a job search I'm expected to go to more than the two pre-approved businesses per three or four hours I'm out there, but there's a catch: I can only go into businesses if and only if I document the business name, address, whom I spoke with, phone number, time I arrived/left, and provide proof I was there—not always an easy task, especially considering that threat of “being sent back” if caught deviating. So, when a business doesn't have an application, a business card, or even a matchbook with their number on it, one hopes that at least there'll be a napkin or a take-out menu or something—either that or hope that the work release will believe you that they don’t. Therefore one quickly becomes adept at looking in windows and scanning for stacks of business cards before stepping one foot inside. A large percent of the guys who go to work release don't make it through their 4 to 6 months without being sent back (it seemed, from my stay, that it was about 50 to 60 percent, but after talking with the staff, they said it’s lower). Granted, a high proportion of them go back for just that—being high, but there are still the deviators who do not pass go and go directly back to jail or prison. But, yeah, drugs/alcohol tops the list, followed closely by having/using a cell phone. And bringing tobacco into the facility.

During that first week of job searches I, of course, got lost in Seattle essentially daily and asked people on the street for directions, but the first time a guy pulled up his Google Maps app and tried to hand me his phone, I put my hands up in the air and spewed forth how I wasn't allowed, you know, like I’d be shot for typing in an address on a phone.

![]() |

| Job Searching Near the Bubblegum Wall |

But the one thing I quickly learned whilst job searching was that many businesses look at you like you're from another century when you ask for an application because it's, of course, almost all online now. But when you're forced with the threat of a really rather serious—or else—to go job searching for 7 hours a day, 5 days a week, and only 9 of those 35 hours can be online at the WorkSource, you quickly either accept the first job offered or you commute daily to Stressville like I did. I will give the DOC credit for one thing, though: they instill, with this job search schedule threat, a great job hunting work ethic; I concur that when looking for work whilst unemployed, it should be a full-time job. Certainly some of my fellow residents have never put that much concerted effort into a job search (and, sadly, many still don't—instead taking the first food service back room job or end up sorting through garbage for minimum wage), but still—it's a rare good DOC idea.

QUASI-FREEDOM Day 9:

OH, MY FEET. Blisters. On my feet. On my heels. On my toes. Between my toes. Brutal blisters that Band-Aids don't stop from hurting and which make walking beyond painful. Blisters that soon callous, then re-blister in new spots. Blisters that make one plan their job searches within a very short distance.

A FEW NEW THINGS SINCE 1996:

- AUTO-FLUSH TOILETS nearly everywhere. Auto-sinks nearly everywhere. Auto-towel dispensers nearly everywhere.

- Cotton-candy pink, Smurf blue, and royal purple hair colors on nearly all age groups.

- Yoga pants.

- Mini-mini cars. (Car2go’s are adorable, I just want to pick ‘em up and rub their bellies.)

![]() |

| SuperMini Car2Go Equals Adorable |

- e-books/e-book readers.

- Nipples on mannequins (not in a sex/lingerie store).

- Dorsal fins on cars (apparently for Blue Tooth devices).

- Talking crosswalks, with seconds counters, with attitude (WAIT! WAIT!).

- e-cars.

- The 12th Man cult of the Seattle Seahawks with “12” or the blue and teal colors of this football team nearly everywhere.

- Credit-card street bicycle/helmet rental stations.

![]() |

| Bikes for rent in Seattle |

- Legal marijuana, medicinal. Legal marijuana, recreational. People smoking pot at bus stops, next to kids. Kids smoking pot on the bus, not realizing their joint is still lit.

- e-bikes.

- Gluten-free markets.

- Patterned yoga pants.

- Earlobe stretched—do you even call it—piercings. (I had seen a few guys in the last few years who had these but because they weren’t allowed the jewelry/stretchers, their earlobes hung deflated, and sad.)

- Flagpoles (without flags) on shopping carts.

- Blindingly bright white headlights. Strobe-like/annoying cop car lights.

- CCTV cameras nearly everywhere—so much for thinking I’d not be on camera all the time after prison.

- The sheer quantity of facial (as in cheeks, nose, lips, etc.) piercings.

- Advertisements on grocery store floors.

- Sidewalk pet poop baggy dispensers and poop receptacles.

- Flavored bottled water.

- Phỏ-punned restaurants. (What the Phỏ, Phỏ Yummy, Phỏ In and Out, etc.)

- Recycle bins on downtown streets next to garbage cans.

- Blow-up Christmas yard decorations.

- e-cigarettes.

- ASCOB yoga pants.

![]() |

| The Hidden Needle |

QUASI-FREEDOM Day 13:

“SO IS THAT an official job offer,” I told the hiring manager sitting across from me after a half an hour interview.

“Yes, yes it is, Jeff. We'd like you to take either the commission on-call jewelry sales job working for me or that non-commission position in women's dresses. Which suits you best?”

I answered him and he was fine with my choice, and here is where I took a deep breath and, in a serious tone, put to use the advice my Veteran's Affairs (VA) rep had given me just the day before and said, “I need to put something on the table. About a year after I was honorably discharged from the Army I made the biggest mistake of my life and, unfortunately, committed a felony. Since then I've remained working, completed my AA, volunteered for two non-profits, and am four classes away from completing my bachelor's degree. But I am currently in work release. I fully understand if [well-known retail chain] isn't able to hire me, but I needed to be up-front with you about this.”

I then answered his uber-polite request to know what the crime was and I answered him, adding,

“Thankfully, no one was hurt. Do you think this is going to be a problem?”

“Had you've chosen the commission job with jewelry it might've been a concern to the background check people, but I don't think it'll be an issue for the women's dresses department.” I started working there a few days later; I was more than thrilled and took copious notes during my first couple of days of video training and I'm not sure the smile ever left my face.

QUASI-FREEDOM Day 17:

ON MY SECOND and a half day with—um, let's call them Das Schnäppchen, I was wearing my newly purchased uniform of black shirt and pants and I had just finished my cash register training (far less interesting than the video on what to do if a “shooter” comes into the building—run, hide, and then, if needed, fight, in that order). I did the cash register training in an empty room on one of the eight machines there next to yet another computer-screen “trainer” and I was on my way to take my lunch when a gentleman from Human Resources (HR) asked me to come into his office where he asked me for further details of my crime.

I provided all he needed and, for about four minutes, expanded, in detail, all of my rehabilitation. He sent me back and said he'd contact me after he and his two fellow HR co-workers had a meeting about me.

Two days later my Community Corrections Officer (CCO) called me into her office and told me that the HR guy from Das Schnäppchen said, “We don't work with people in work release.” And she asked him if I could work there when I get out and he, apparently, just repeated that, “We don't work with people in work release.”

Although that wasn't ideal, as I told my VA rep after she sent off an unhelpful (for me) but highly encouraging (to me) email to the HR guy prior to the HR meeting about me, “I look at it this way: this was better than a mock interview because there was pressure to do it right without a 're-do' and I did well enough to actually get the job, so I'll just do it again.”

But hey, I did get paid to watch videos for two and a half days and besides, the jokes about me working in women's dresses were sadly stale and unoriginal after day two anyway.

![]() |

| My Bay Window and Part of the View I Have of the Puget Sound |

QUASI-FREEDOM Day 25:

MT. RAINIER EXTENDED all the way to the ground.

QUASI-FREEDOM Day 26:

TECHNICALLY I WAS days away from being sent back for not having a job yet, but was it 4 weeks or 30 days that was the ultimate deadline? Were they going to tell me I had two days left to get a job? Would it matter if I was hired, but my start date wasn't for a few days? And did I get credit for the job I had but didn't quite get fired from? (Another reason to be sent back for, potentially.) These questions, and where I was going to go to work, caused me more duress than each night from being 6’2” tall trying to sleep on a 6’ long bed with nowhere to poke my feet off or through and repeatedly being awakened by leg cramps which I was barely able to bite down on in the middle of the night to stop from waking my first roommate since 1999.

Thankfully a new friend took pity on me after seeing my portfolio of artwork and got me a job painting houses. Though I never got to be as fast as the great guys on the crew, I was often tasked to do the “artist” detailing that others, I think, didn't have the patience for.

And not only was my starting pay higher than the 2.5 day job with Das Schnäppchen, but I got my first ever retroactive pay raise (20 percent more) after the first two weeks on that first paycheck and I got another raise shortly afterwards. But best of all, the stress of being sent back was gone and, since I'd been upfront with the lead-man from the initial phone interview that I was actively looking for other work, I was allowed to work the days and hours that fit my interviewing and still be employed for enough time to not only satisfy the DOC and keep me from the stick of being sent back, but it was enough to qualify for me for the carrot of being checked out of Work Release like I’m a library book to go out on my first “social” visit.

![]() |

| On a Social Visit to the Seattle Art Museum with my Mom |

FIRST EVER INTERNET PURCHASES:

- TWO PAIRS OF glasses, much needed.

- A stack of books the DOC wouldn’t ever let me buy, much desired.

- A device I’ve coveted for the 10 years or so I’ve known of its existence and very much needed: nose hair trimmers.

QUASI-FREEDOM Day 42:

AFTER ABOUT 6599 days of not ever being able to go to anybody’s home, after seeing pictures and hearing descriptions of homes and pets, and after undeviating behavior for not just 42 days of quasi-freedom, but for however long it was that qualified me for Work Release, I was approved to be checked-out, yes, like a library book, by my sister as long as I was returned within 10 hours. The late fee is, you guessed it: being sent back, or at the very least, like if under 15 minutes late, losing the privilege of going out on these “socials.”

But to remain eligible for them requires a combination of things: infraction-free, be at Work Release for 30 days, turn in your first (and all) paychecks (because Work Release costs $14.50 a day, whether you’re working or not), and you must work at least 32 hours in the last 7 days. To qualify for three socials, not just two 10-hour socials per week, one must work 40 hours or more in the last 7 days. I, technically, might not have qualified for this first social visit when I did (and maybe ought to have waited a week or two to stay all “legal” but I, um, creatively interpreted the rule) because my painting job only paid us every two weeks but I turned in that 2.5 day job paycheck from Das Schnäppchen and just hoped that they’d count it. They did and I was eligible for my first time going to my sister’s home, see what will be my own room, and—something I’d worried about— something my sister did think I was ridiculous for when, prior to coming over to her home, I admitted that I was slightly nervous about meeting her four dogs and begin the process of winning them over and having them accept me as family. I was willing to bribe them with bacon if need be. Thankfully, though, they just want attention, petting, and, obviously feed them some SNACKS!

Over 18 years I’d seen the prison’s drug dog many times (and been “hit on” by it, falsely, as well) and a few times some blind church guy would come in and let us pet his guide dog if he didn’t have the guide-harness held. But it’s not even the same as getting on the floor and petting a pack of adorable and friendly dogs. Nothing is.

Touch, actually, is a strange thing. There’s a limited number of things one has the opportunity to touch in prison and my sense of touch (at least for the “exotic”) atrophied but, thankfully, I’m in physical touch therapy—trying to rehabilitate my fingertips to the idea of touching tree bark, the wild grasses grown in concrete planter’s pots in downtown Seattle, soft fabrics, and, yes, the soft fur on the top of Mr. Man’s head. I’m working my way up to human skin.

In prison I was one of the lucky few who were allowed to have trailer visits. This was where my family would come bring food in and we’d make a weekend of eating, talking, playing games, eating, watching DVDs, and eating. Basically just being a family. Connecting in an environment that, unlike the visiting rooms, isn’t tyrannical and almost clinical. But even then, during trailer visits, it wasn’t quite a true vacation from prison. Firstly, the trailers were physically behind the walls so the view was the same: a 30 foot high old, crumbling, weed-covered wall that despite its age and wear, still kept everything without wings, a tail, or a badge, solidly from leaving. Secondly, the guards would “count” us in two ways: one by me standing outside and waving howdy doody to the guards in the tower and, two, by coming in for a “health and welfare” check—these would alternate and come at times that would exasperate my early-to-bed mother far more than me, perhaps because she wasn’t as used to dealing with an inflexible, uncaring bureaucracy.

![]() |

| My First Convertable Ride |

But a social visit is entirely different. On my first one I went to my sister’s and did chores like sweeping her roof of pine needles and moss (and while that might not sound like a rowdy wild time, after being what internally has felt like a burden upon my family for over 18 years, I am glad and honored to be able to help out first where I can…time permitting). I also got to ride in her convertible and obviously eat, a lot (some important things don’t change). Eat so much (and such rich food) that I, yes, did get back to the Work Release and, later, puke up all that great food; it tasted better the first time.

![]() |

| Earning my Supper on a Social Visit |

Essentially, though, what socials do is let me feel like I’m a fully-functioning, contributing non-caged, actual human who has loved ones that don’t need supervision to be around. On my first social visit I asked my sister to bring a camera. Because after over a month of zipping around and across not only downtown Seattle, but, as I grew more comfortable (in thinking I could get back in time), zipping all around from Burien (down south) to the U district (north) to west Seattle (that’d be west) and to Bellevue (you guessed it: east) with not only my expanding job search (now using that bus pass to its full advantage and not just going to places within walking distance) but also because of my new job as a painter, I had seen so very much that I wanted to document. Hence the camera.

![]() |

| Stacking Wood on a Social Visit |

Getting sent back is the threatened stick, but socials, to be sure, are the biggest carrots the DOC has to offer. Even given the conditions that some complain about; heck, before I got to Work Release, some guys told me that it’s a rip-off and a scam. I currently pay for my stay here as a “resident” at Work Release—and am happy to pay it (though, it should be noted that those who aren’t happy typically have massive chunks of their checks taken due to debts and are left with very little). But, yeah, I’m happy to pay $14.50 a day for the right—nay, the privilege of earning at the bare minimum of $9.32 an hour for 32 hours a week to earn my socials.

![]() |

| I Guess it is True |

But, at the risk of getting political, let’s, for a moment, expand this outward: it costs $46,897 to house an inmate in Washington State [figures from

2010]. Now, while I don’t believe we should be making a profit from the incarcerated (and I’m sure they don’t…well, other than all the jobs generated, but that’s another question), the fiscal concern is often brandished about with respect to incarceration. Yes, it absolutely is expensive—more so the higher the security level (though that’s often a play by the guards’ union to get more workers at more pay to do less work, but that, too, is another question and, admittedly, hearsay and conjecture). But according to the RCW (Revised Code of Washington) I’ve read prisoners are eligible for Work Release at 12 months “to the gate,” as it’s stands, not the 6 months that is currently in practice. If the DOC would invest in more Work Release facilities at an initial large investment, to be sure, it would help pay their way two-fold: residents would help pay their way and they’d not be incurring the heavy expenses that come with an actual incarceration, prison-style. My napkin math says that for six months a resident will pay $2,610 and for a year $5,292 and while that’s not much of a dent in the $23,448 for six months of incarceration or $46,897 for a year, because there are less staff, no walls, and no guns, the actual cost of incarceration will be massively lowered. Just a thought, people, just a thought.

Besides, if the DOC did anything besides a lame feign towards rehabilitation it’d not only reward more guys for longer, with the carrot of social visits, but help them build a nest egg for themselves for when they get out. And that’s possible because the Work Release facility is super strict on how much of your own money you’re allowed to spend while in here and certainly it’s going to reduce recidivism by giving guys more (of their own hard-earned) money upon their release.

![]() |

| Me and a 10 Dollar Hoe |

QUASI-FREEDOM Day 93:

WITH FULL PERMISSION from my Community Corrections Officer, I was able to go to my first “outside” University Beyond Bars event and speak to all the donors who so generously support the UBB. I was slightly nervous there and a few of my jokes fell flat (as they should since I’m only percentage funny—oh, I’m funny, but only a percentage of the time), but overall it went well and it was great to be able to get hugs from teachers who have known me for years.

THINGS I HAD TO RELEARN (OR LEARN FOR THE FIRST TIME):

- ADJUSTING TO THE harsh, almost overwhelming metallic taste of non-plastic utensils.

- How to chew gum (not how to chew it, but what flavors to pick from…okay, maybe a little bit how to chew it as I’d not chewed any gum for over 18 years—and I’ll admit, reluctantly, that I did bite the inside of cheek…and lip).

- That you shouldn’t click on a link INSIDE an email, but instead put it in the link up top (who knew that malware was buried in a link).

- That websites can be counter-intuitive and not make it easy to go backwards: I sent a birthday gift to Scotland which arrived addressed in my name because “the internet is hard,” I told her, but really because I couldn’t figure out how to change the shipping address name be different from the billing name.

- That food is hot; not just an industrial kitchen grade hot, but steaming, burn-the-roof-of-your-mouth hot.

![]() |

| The View from my Bay Window |

QUASI-FREEDOM Day 127:

AFTER THE PAINTING job became less than full time I had to get another job. Even though I’d created a position in that company which had never existed before (office administrator, bringing the company into the computer age), I needed more work not just to satisfy the Work Release, but also to qualify for the, to me, all-important social visits with my family (I missed out on one weekend because I didn’t have enough hours when my Mom was in town and that perturbed me greatly). So I took one of those jobs that I knew would hire me because they had other guys from two different Work Release facilities in Seattle working there. I was hired on the spot by the owner (who, I later found out, hires essentially everyone who can speak/read English) and I basically made myself a full-time employee by telling the secretary, after I’d started and was discussing my hours, that I only took the job because I was expecting it to be full-time.

But I have never felt so…creepy doing a job before. Sales, in and of itself, isn’t icky—if you’re providing a good or service that people want, it’s all good. But this job causes people to cry and caused me to cry, too.

A PUBLIC SERVICE ANNOUNCEMENT: FOR THE LAST month of my quasi-freedom I’ve done maybe not a horrible thing, but certainly a bad enough thing that doing it makes me feel not just icky, but like I branded my karma with some irreparable harm. But I’d like to now, for you, dear reader, at least try to chalk up some good karma points—I doubt it’ll make up for all the harm I was paid to do, but still.

After my painting job dried up to non-full-time status I took a soul-sucking minimum wage job as one of those very annoying people that call you up (with caller ID blocked) asking for money, even if you’re on the national Do Not Call list (“Thankfully charities are exempt from that so that we can raise needed funds for…” reads the rebuttal). Yes, I’m one of THOSE people. Granted, this may not be the worst job there is in that we’re not rude, just insistent. Thrice insistent. As in, “Oh, I’m sorry to hear that you’ve been out of work for a year, just got diagnosed with leukemia, and your dog just ran away—but you actually don’t need anything now to help out…” The one and only thing we’re allowed to end the call for without rebutting twice is the death of a spouse (though I’ll always feel like there’s some slime on my soul for convincing a son to donate in his mother’s name after she lost her husband, his step-father). But in a hope that there might be SOME good to come of all this…here is what I’ve learned that I hope might help you:

There is no rebuttal to even a polite “Take me off your call list”—but please note: there are different versions of this. The “simple” one, at a less scrupulous business like where I worked, gets you off their list for about 70 days and then they’ll call you again. Or at least that’s what the owner of this company said. The more complicated one requires one of two things: (a) either get loud and livid or, better yet, (b) take a few minutes to ensure they absolutely never will call you again by acting like you’re interested, get all the required info (full names, physical address, phone number, registration number with the Secretary of State, tax ID number) and then threaten to call the Attorney General—trust me, they listen to that particular stance. But if you say “take me off your list” before you know who they are, why would they need to take you off?

Always, always, always ask for a specific percentage of how much money actually goes to the charity. Do not accept a paragraph answer that lawyers you away from your actual question. Repeat yourself until you get an actual number. Yes, a for-profit company making money for a non-profit deserves to make some money, I suppose, but do you want to support the charity or the people making money off of the charity? If you truly want to help them, get the info (at this place they’d only reluctantly give out the website info so that people could donate directly as they didn’t get a 60% cut of each of those dollars), and donate directly.

Remember, three is the magic number. Unless there’s some special circumstance, if you politely say no three times, the call will end. Once gets you to the first rebuttal (and there will always be a rebuttal to any “reason” other than “I’m not interested”), twice gets you a second rebuttal (often at a cheaper price), but the third no lets them know that you’re not budging and they’d rather spend their time on the weak-willed; and don’t doubt that there are some who are—on our “taps” calls (a disrespectful label as it’s used as a way to describe people who’ve given in the past and not only do we “tap” them again, but we keep on tapping them until they tap out) we try to only ever talk to the spouse who gave in the past; the other spouse is the one to avoid as they’re usually the one to say, “Take us off your list.” One guy answered my initial greeting with, “No. No. No. There, you’ve heard three of them, now go on to your next call.” This made me laugh—and remember, not everyone who works at such places are soulless.

In four weeks I saw at least two dozen people get hired and then get laid off if they couldn’t get a sale in three 4 hour shifts or, more likely, quit because they simply couldn’t deal with either that much rejection or that much heartache. I will admit, it was hard hearing my first woman cry on the phone to me (her husband just lost his job after being diagnosed with leukemia—but she WANTED to give, she just couldn’t and this caused her to cry and I couldn’t do anything but offer hollow words; talking about it later with someone close to me she told me it’s sometimes easier to breakdown to a stranger, because there’s no pressure to “keep it together”), but it’s also not easy crying on the phone when someone tells you a heart wrenching story. For me that came when a woman told me that she and her husband just lost their business—it’s weird, there were much more intense stories told to me (often within 3 minutes of a conversation), but this one got me choked up and made me say something, I hope, consoling and then ruin the next call because I was all choked up and I was glad the guy hung up so I could go wash my face and try to compose myself. By all means, some of the people there say some horrible things when they hang up the phone about the donors, but not everyone is like that; some are just trying to make some much-needed money in a legal way. And many of them, me most definitely included, will consider their brief stay there with that necessary job as one of the worst jobs they’ve ever had.

![]() |

| Seattle's Columbia Tower (Had an Interview on the 42nd Floor) |

A NOTE ABOUT ANONYMITY: AFTER A COUPLE of months and at least a dozen interviews that went, as far as I could tell, fantastic, but without getting many call-backs I began to wonder aloud if it was maybe more than, possibly, being overqualified. I then Googled myself and saw that if you typed in my first and last name plus Seattle, up popped Minutes Before Six (MB6). And while that’s great for many ways (because I’m proud of what MB6 is doing and stands for), I felt like it was possible that potential employers were Googling me and finding out, without doing an expensive background check, that I’ve been in prison (and for a very long time, for a very serious thing). And, if that was true, then I was maybe making it far too easy for such potential employers to dismiss me and my abilities without giving me a chance to prove that I’m not that dumb 23-year-old kid anymore.

![]() |

| Pike Place Market Graffiti |

![]() |

| Pike Place Market Graffiti, My Contribution |

All that to say this: regretfully, for now, as I’m looking for (as I say in these endless interviews) “not just a job, but a career,” I have removed my last name from this website. Certainly anyone worth their investigative dollar would still easily find out that I’m a felon and what those felonies were, but there’s no sense in doing their job for them. Although I’m doing this for, I think, sound reasons, I do feel selfish for this choice because not everybody gets to (potentially, partially) hide from their past. In fact, I imagine that there’s a few readers of this site who read this site because many of their people writing it can, and do, well, speak freely in a way the free often can’t, but I hope that my dropping my last name will allow me to continue to speak truth to power, and not just cower away from the potential consequences for speaking up.

![]() |

| Seattle's Wheel at Dusk |

QUASI-FREEDOM Day 152:

IN BETWEEN MY split-shifts of a soul-sucking job (for which I was most grateful to turn in my two weeks’ notice), I filled out after-the-fact application paperwork for my very first job with full benefits and a 401(k). I smiled when he had me only complete the first and last half of the application, skipping over the parts he’d crossed out which included that dreaded question which has killed many a job for me (even after truly killing it in an interview): “Have you ever committed a felony?”

Oh, sure, there are other phrasings to this question—including the “in the last 7 [or 10] years” one—but this wasn’t the first time I was instructed to skip this. No, when I got that 2.5 days long job at—oh, what’d I call it?—ah, yes, Das Schnäppchen, the in-store, on-line application I filled out had a peculiar (to me, then) phrasing about this question. It said: CRIMINAL BACKGROUND INFORMATION: If you are currently residing in or applying for jobs in HI, MA, MN, Newark NJ, Buffalo NY, Philadelphia PA, RI or Seattle WA, the below questions should not be answered with a “yes” or “no” but instead with “I currently reside in or am applying for jobs in HI, MA, MN, Newark NJ, Buffalo NY, Philadelphia PA, RI or Seattle WA.” The reason for this is that there was a grassroots campaign to “ban the [criminal history] box” on applications so that convicted felons could at least get an interview before that stuff came up.

Seattle recently passed the “

Ban the Box” law. This was, as I understand it, because of the

movement of the same name which is all about allowing felons at least a shot at an interview because if they see the box checked, “Yes, I have committed a felony” the application obviously gets chucked, all too often. Absolutely there are jobs in which I’ll never ever qualify for (and I’ve still no idea what about my résumé that draws financial planner/insurance recruiters to me like my eyes to yoga pants—even but for a glance), but I’d still like to interview for the others.

True, there are jobs in which I get that I have forfeited my right to try out for. But there are still a lot of other jobs which, when I checkmark that box (and often have to describe what the felonies were), I know I’ll never be considered for—not because I’m not qualified or because I’m barred from doing that job, but because—from their point of view—why bother? Maybe it’d be different if the economy was hiving and there wasn’t a very low 4.6 percent in Seattle as of September 2014 [source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics] of busy little bees unemployed, but it’s an employer’s market, so companies get to be choosy. Also, because the law isn’t exactly fully know about, let alone enforced, companies still have these questions in their applications.

But I just hope that the smirk I had on my face signing my hiring paperwork doesn’t get wiped off by yet another background check although thus far they’ve all been conducted (and paid for) after I admitted I was a felon; it’ll be interesting to see if they go back over 18 years if they’ve not been told ahead of time that there’s a there there. But it was certainly pleasant to be offered a job after an interview (I’ve had over half a dozen of these job offers in the last 5 months) and not have to pause, shift tones, and “need to put something on the table.” Maybe now, finally, I can just do the job I was hired for. Do the job I know I’m capable of. Do the job long enough, good enough, professionally enough that by the time any background check comes back they might just say, “Hey, he’s a worker—let’s keep him.” One can always hope, right?

![]() |

| Out Pumpkin Hunting for Halloween |

QUASI-FREEDOM Day 152:

AFTER A LONG 18 years, 4 months, and 20 days, I woke up (early, obviously) ready (quite obviously) to get out of prison. After I gathered up all my bedding, washed it, had my room checked for cleanliness, gave the rest of my stuff I didn’t need away, and signed myself out, I grabbed my backpack of stuff and walked out the front door, a free man. Freedom. Is there any word better than that? Is there any better feeling than that? I don’t know, but I’ll let you know in part two, when there won’t be any “quasi-” to this freedom.

![]() |

| What I Actually Wore Out on Halloween To and From Bishop Lewis Work Release (sans Dog) |

—December 2014

![]() |

Jeff C.

jeff@minutesbeforesix.com |