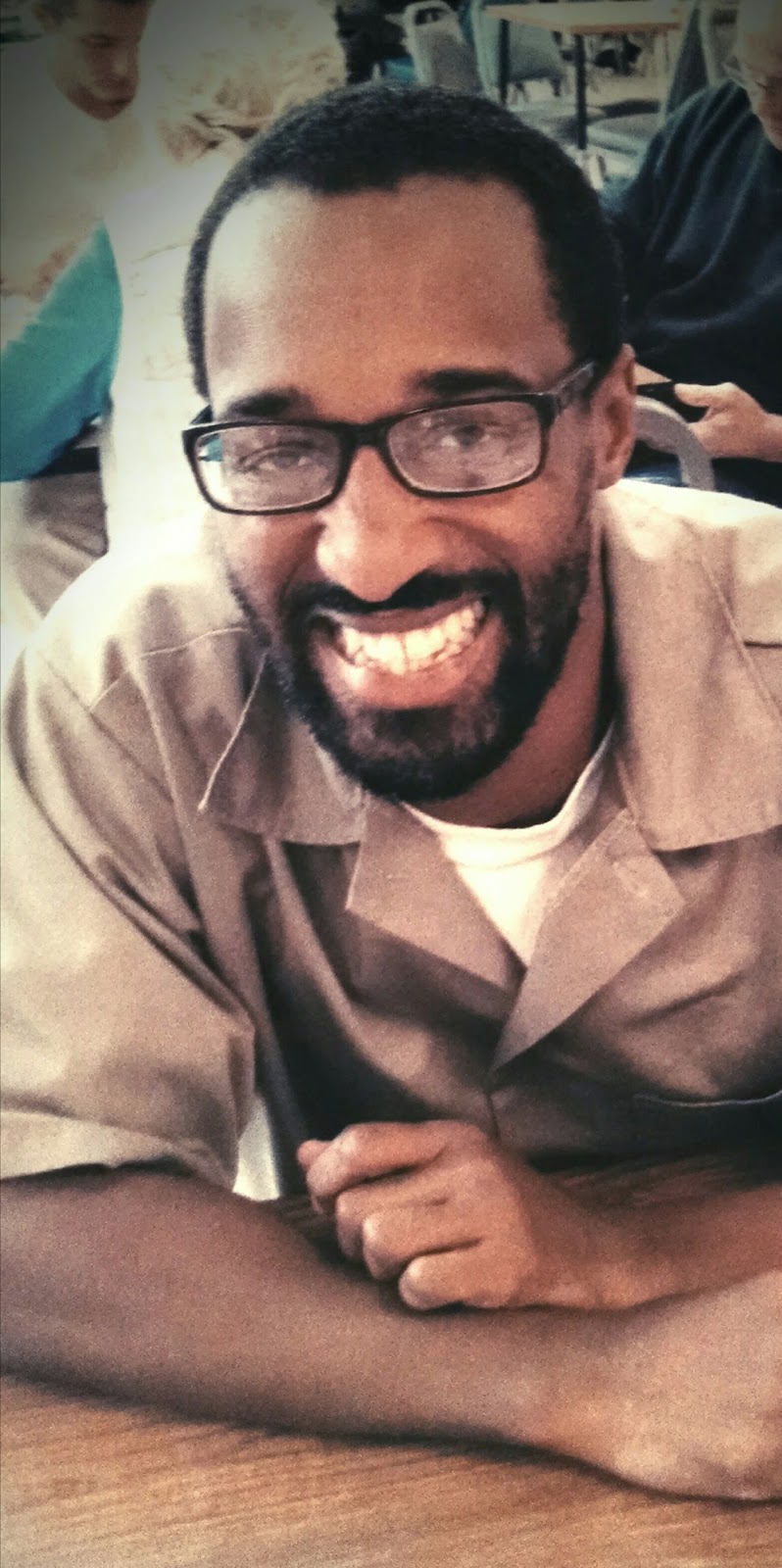

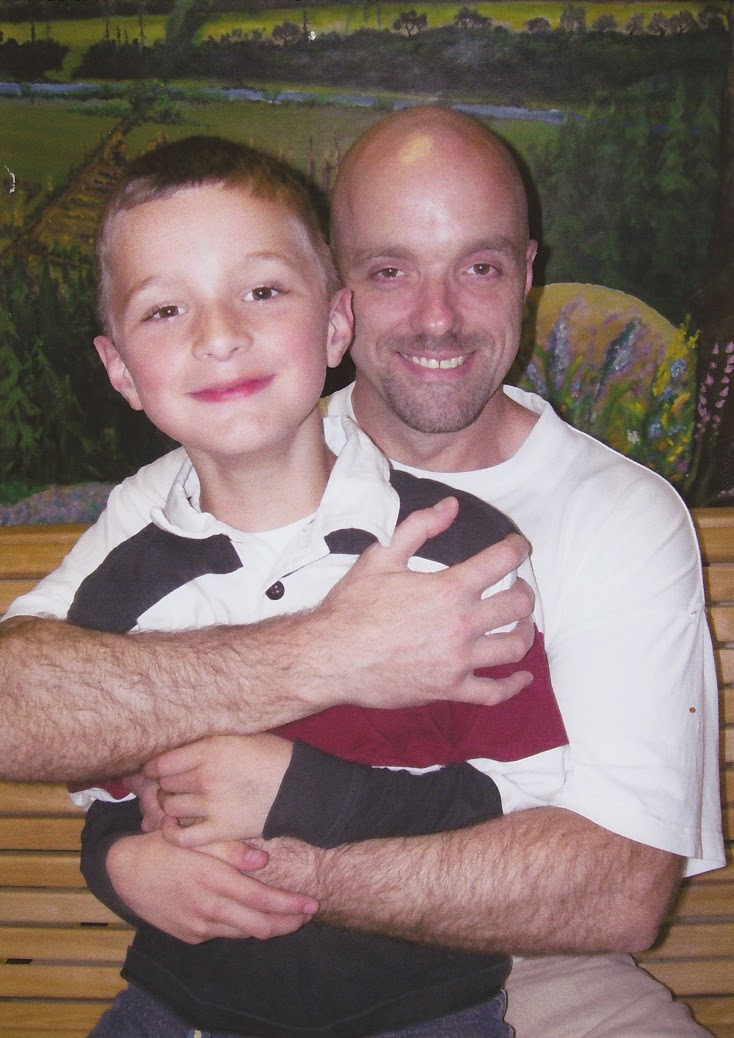

Bill Van Poyck was executed by the state of Florida on June 12, 2013. This story was submitted by his loving sister, Lisa, and we consider it a great honor to be able to share it with you.

A story by William Van Poyck

On a quiet, humid night framed by a rising gunner’s moon, Percy Brown, of dark hair, bright eyes and reasonable intelligence, formerly of sound mind and spirit, was questioning his judgment, if not yet his sanity. Swish, swash. Swish, swash. Back and forth, four strides to the stretch, Percy paced the concrete floor of the small room situated in the hulking red building, laid brick upon brick among the sprawling assembly of like structures. The dark complex lay huddled like a sad story, deep in the pine tree forests skirting the Alabama state line. Swish, swash. Swish, swash. He felt his bare, calloused feet rhythmically chafing like dry bark on the worn floor.

Percy paused, his eye catching one of the hundreds of lines of graffiti drawn, burned, scratched and gouged into the concrete and stonework: Today a rooster, tomorrow a feather duster. His brief smile was interrupted by a noise. Percy hurried to the solid steel door, cocking his head attentively to listen through the chest-level, steel-barred opening. Voices. The clank of heavy steel. The jangle of large, brass keys. Leather soles squeaking on linoleum. Percy’s gut leaped. It was almost time. He again checked the position of the towel on the floor at the base of the door. Surely nobody on the other side would be able to see it. He dodged to the rear of the room, banged hard on the wall several times, and scrambled up on the ancient, stained porcelain toilet, then up on an equally ancient sink. Whispering hoarsely he spoke into the grimy wire mesh welded across the air vent.

“Winky. Winky!”

“Yeah,” came a muted reply after a long moment. “Who’s calling my name?”

“It’s me. Listen.”

“Is that you Sheila? Sheila? Sheeeeila. Help me, Sheila.” The voice was distant, lost, as though spoken from a deep well.

“Winky! Dammit, it’s me, Percy. Listen to me!”

“Yeah.” There was a long pause. “Percy.” Another pause. “OK. . . . Yeah . . . I know you, Percy. Is that you, Percy?” The voice was monotone, flat.

“The cart is coming. Don’t forget what I told you. When I give the signal, you do your thing. Don’t forget. It’s important. You remember what to do, Winky? You hear me, Winky?”

Percy balanced on the rim of the sink, stretching up, turning his ear to the vent, wincing as he felt his stitches pull taut.

“Is that you Sheila? Help me, Sheila.” The keening wail echoed from the well.

Percy cursed under his breath. It was time. His wrenching gut tightened another notch. Climbing down, his foot slipped on the wet enamel and he lost his balance, falling backwards, wind-milling. He hit the floor hard.

The cart slid up in front of the door, pushed by a heavy-set, grey-haired female nurse shadowed by a very large man in a tight-fitting white uniform. Both stared at Percy.

“What’s wrong with you?” The orderly wondered loudly. “Why did you jump off the sink?”

“I fell. I didn’t jump.” His leg hurt where it had hit the floor.

“You jumped. I saw you.”

“So did I,” the nurse added, nodding her head.

“You trying to kill yourself again, boy?”

“I fell.”

“What were you doing up on that sink?” the nurse asked, pointing with her chin.

“Yeah. What were you doing on the sink?”

“Nothing.”

“Nothing?”

“Nothing. Look, just give me my stuff. I wanna go to sleep.” Percy forced a crooked smile.

“I think maybe you need a shot. To calm you down. You look excited. Doesn’t he look excited?”

“Yes. Looks upset and excited to me,” the orderly agreed, fingering his brass keys.

Percy’s stomach knotted up even more. “I ain’t excited. I’m calm as the goddamn Rock of Gibraltar. Now give me my goddamn medication so I can go to sleep.” Percy did not want a shot.

“Don’t you cuss me,” the nurse said.

“Don’t you cuss her.” The orderly took a heavy step forward.

“I won’t take sass from you. You’re excited. You need a shot.”

“Look. I am not excited. I do not need a shot of Thorazine.” Percy was breathing harder.

The nurse began pulling out drawers, searching for one of her pre-loaded syringes. Percy licked his lips. It was a salient moment, loaded with danger, and he stood still as a fence post, sorting his options.

“With thee all night I mean to stay,

And wrestle ‘til the break of day.”

Percy blurted out the words in a sing-song voice, even as he wondered where they came from. Both the nurse and orderly looked up, staring at Percy.

“Look, I ain’t taking no shot. I’m not one of these lame-ass crazies you love to jump on, tie down, beat up and shoot full of Thorazine.” Percy backed up, spreading his feet. Thorazine shots were very painful and knocked you out for two days. Percy’s butt cheek still ached from the last shot. He was determined to take no more.

“You’ll have to go get the goon squad ‘cuz I ain’t taking no damn shot. I know damn well you aren’t even supposed to be giving those shots without prior written authorization from a doctor. Ain’t no doctor here.” Percy paused, leaned forward slightly and lowered his voice. “And, let me tell you something, I don’t have no public defender, I have a real lawyer, and if I get a shot I’ll be reporting both of you, and my lawyer will be down here raising hell. I know what you two have been doing around here and I’m just dying for an excuse to tell it all to the Department of Professional Regulation, the Inspector General’s Office and the damn newspapers. Just try me.”

Percy stood firmly, feet braced, heart pounding. He was wary, upset, angry. He was excited.

The nurse and orderly exchanged glances. In the silence Percy heard her labored breathing. Next door, Winky was mumbling, talking to someone or something. This was dangerous, Percy knew, for he had seen what they could do. Percy felt as though he was posted at life’s window, watching a scene unfold. Abruptly he thrust his hand forward, palm up. Finally, the nurse handed him a paper cup containing his prescribed psychotropic cocktail of Haldol, Stellazine, Mellaril and grapefruit juice. Powerful drugs. He, like everyone else, was also supposed to receive Benadryl, to counter the horrendous physical side effects, but it was seldom administered. Percy took the cup. The nurse and orderly stared at him, eyes glittering in the fluorescent light.

“THANKS FOR MY MEDICATION, BOSS MAN!”

Percy shouted out the agreed-upon signal, while slowly raising the cup to his lips. He waited for Winky to scream, the agreed-upon response to distract the nurse and orderly, permitting Percy to surreptitiously spit the medication onto the towel. . . . Nothing. . . . The cup touched his lips. . . . The nurse wrote something in Percy’s chart, but the glaring orderly locked eyes, his face flushed red, neck bulging. Percy took the liquid into his mouth, feeling the bitterness wash over the back of his throat. He made an exaggerated swallowing gesture, tried to smile at the orderly. Silence filled the hallway as the orderly scowled back. Percy felt like a chipmunk.

“Swallow!”

The liquid burned all the way down as Percy reluctantly swallowed.

“Step closer! Open up!”

Percy stepped forward. He knew the drill. Percy opened his mouth, stuck his tongue out and rolled it around in the standard fashion. He never saw the orderly’s nightstick shoot through the door opening, only felt the impact at the base of his throat, driving him backwards, leaving a choking gasp in his wake.

“Punk!”

When Percy, back against the wall, looked up, they were gone. He gingerly felt the soft spot just below his Adam’s apple, swallowing tentatively. When he heard the cart leave Winky’s cell, Percy crouched at the toilet and jammed two fingers down his throat. He gagged, coughed, sputtered, but did not vomit. After a time he gave up. Cursing to himself he slumped down upon the sagging bunk. The cold fingers of resignation pulled at his spirit as he anticipated the medication’s inevitable course, flowing and whistling down the staircases of his body, through the corridors of his mind, seeping into his psyche like red-eye gravy on cat head biscuits. Within an hour Percy would be unconscious. Tomorrow, after perhaps sixteen hours of sleep, he would awake, spacey, groggy, lethargic. Later, the terrible muscle cramps and spasms would humble him further.

Percy’s gaze slid around the bare cell, gliding over the cobbled graffiti, the variegated stains impregnating walls and ceiling, the naked, solitary light bulb defiantly clawing at the pressing darkness. Cast shadows abounded, mottled, leavening the air with a weighted, tangible scent of bleakness. Only the tired floor, worn smooth by legions of shuffling feet, remained free of blemish, save for the rough corner patch bearing the unmistakable marks of some desperate soul sharpening steel. Percy sighed.

At least, Percy reflected, it was not Prolixin. Six months earlier, following his arrest, when he first purposed to play crazy, he was strenuously warned by fellow prisoners to avoid Prolixin shots at all costs. When Percy was, in fact given a shot, he learned why. Each shot, he was duly advised, lasts two full weeks. The first three days were uneventful but on the fourth, like clockwork, the drug kicked him like a government mule. At once, Percy felt the change. It began with horrific muscle contractions and spasms, locking his jaw in a clenched position and pinning his head to his left shoulder. His arms drew up like a spastic’s and he drooled uncontrollably. Prolixin’s side effects, he was told, were known to kill, and Percy became a believer. The prisoners called patients on Prolixin “crispy critters,” or “bacon,” for the way their bodies drew up, making them choke and gag like epileptic hunchbacks. Percy, too, drew up, slobbering and gagging on his thick tongue, certain of the nearness of death in that solitary cell. Sometimes the nurses would give him a shot of Benadryl or Akinaton, bringing quick relief for a few hours; more often he was ignored, and occasionally, mocked.

As terrible as the physical side effects were, the mental ones were worse. The drug changed the very way Percy thought, the mental process itself, shaking his concept of who he was, in a manner impossible to articulate to others. Percy became agitated, restless, unable to sleep, unable to sit still, unable to concentrate on any task. A void filled his mind, crowding out all desire for anything, leaving behind only a frightened husk. Like a detached spectator observing a distant phenomenon, some part of Percy recognized that his mind itself, the most basic essence of who he was, had been altered. The fear that the change was permanent terrified Percy. By the tenth day he was debating suicide to escape the unbearable mental anguish. Only the faint, desperate hope that he might return to normal in due time kept him alive. On the fourteenth day, as sure as if a switch was thrown, Percy was suddenly normal again. He was back. At that moment he vowed to die before accepting another Prolixin shot.

Percy blinked hard, fighting the medicine. He ached for a cigarette. Slowly, he lay back, stretching out his frame. His rancid pillow stunk, even through the two T-shirts wrapped around it. But, now it did not matter to him. At that moment the moon became visible in the small slit window high up on the back wall. Percy considered standing up on his bunk, stretching up to take in the vast yellow orb. He had always considered the moon to be a friend, sharing his private solitude with a perfect understanding, devoid of judgment, eager to loan out its soft, limpid light to the whole round earth. . . . Percy blinked again. He was weary. He struggled to keep his eyes open. . . . Having feigned insanity with sufficient dexterity to secure a 120-day order of commitment to the forensic unit of the state hospital, he still had almost sixty more days to go. He wondered if he could make it, wondered if he should. The price was high.

Upon arrival Percy had been placed in an open bay ward with sixty other nut cases, mostly pre-trial detainees awaiting competency examinations. Some were there for degrees of homicide, others for relatively petty crimes like Percy’s, a drunken encounter with a convenience store clerk over some shoplifted pastries that somehow escalated into a felony battery when Percy pushed and ran. Because it would be his third conviction, it was a very serious matter to Percy. At the hospital he quickly learned that prisoners from the nearby state penitentiary, called runners, ran the place with a casual brutality alarming in its arbitrariness. It was a zoo, raw survival of the fittest, pitiless and cruel for those patients genuinely mentally ill and unsophisticated in the ways of doing time. The rank scent of quiet desperation clung to everything.

Late one night, shortly after his arrival, Percy awoke with a start. He stared up into the darkness. Percy disliked going into the large communal bathroom after lights out. Strange things occurred in there, and hearing them was bad enough. On that night, though, his bladder insisted. Treading through the dim dormitory, he stepped into the expansive bathroom, passed the gang showers and stood at one of the urinals. He thought he was alone.

A low, moaning sort of sound cut Percy off in mid-stream. He looked around, saw nothing. Percy strained at the urinal, staring at the wall. The sound returned, sliding along the tiles, echoing off the porcelain, spiraling into a guttural, animalistic quaver that made his neck hairs stand on end. Percy wheeled about, eyes wide, searching the darkness. There, barely discernible in the corner, was a shadowy figure, hunkered down, squatting atop a toilet like a perched bird poised to lay an egg, one foot on each side of the rim. Percy strained to see. The figure appeared to be staring upward, as though lost in a trance. As Percy watched, a long, horrible groan escaped from the figure’s lips, a cry of anguish so wrenching that it seemed torn from his very soul. At that moment an orderly opened a door across the hall and a shaft of light fell through a bathroom window, across the tile floor, and fully illuminated the corner for an awful instant. The horrific scene revealed to Percy would be forever burned into his mind. In that moment of terrible recognition Percy saw Benjamin, a seriously disturbed young man charged with murdering his own mother. Percy’s numb mind struggled to comprehend the scene. Benjamin’s entire hand was inserted into his rectum, his face turned upwards, twisted in torment. Before Percy’s shocked eyes Benjamin pulled out his hand, tightly gripping a handful of bloody offal and intestines. Benjamin’s howl of agony pierced the night air, striking to the quick of Percy’s soul.

Percy ran. He confronted an orderly, yelled, pointed. No big deal, he was told. Benjamin had done this before. He was punishing himself. They took Benjamin away and Percy never saw him again. Percy was not easily shocked, but he found no sleep that night, and for the first time in years he prayed.

The next week an elderly patient supposedly hanged himself, but the word was that the two runners who were terrorizing and extorting money from him had hung him up. The circumstances were very suspicious, but there was no investigation. Percy watched, saw, recognizing that in this place death was just a word.

A few weeks later Percy stepped into the shower only to slip and fall. Bracing his hand on the floor to get up, he found himself covered in semi-coagulated blood, a shocking amount coating the entire floor like a fetid varnish of claret putrescence. A patient, he learned, had castrated himself with a razor blade. The incident had not even caused a ripple on the ward.

For Percy, though, the final denouement came several weeks later. In a semi-private room attached to the ward lay Harold, a state prisoner who, some years earlier, had climbed inside an industrial soap-making machine to clean it. Somehow, the machine was switched on, mangling Harold, cutting off both arms, one leg, and knocking a patch out of his skull. Harold was a mess. Invalid, a little bit retarded, he resided permanently at the hospital. One afternoon Percy was peering through the small patch of bare glass in the painted-over window separating ward from room. It was his daily custom to tap on the glass and call a few words of encouragement to Harold, try to make him smile. On that day, though, Percy was shocked to see Harold being raped by two runners, his feeble struggles for naught. Percy would never forget the forlorn look of resignation seared on Harold’s turned face, the tears streaking down his cheek. The scene sent an arrow into Percy’s heart.

Percy snapped. Picking up a wooden bench from the dayroom, he threw it through the window into Harold’s room. Before the shattered glass finished falling Percy broke off a chair leg and charged through the opening, clubbing the runners with unbridled ferocity. Within moments Percy, too, was beaten down by a flood of orderlies and runners, bound in leather handcuffs and injected with a massive dose of Thorazine. Then, he was thrown into the solitary confinement cell where the friendly lemon moon was smiling down through his narrow slit window.

Percy sighed again. The medication was on him. His eyes fluttered, closed. He was tired of fighting against the drugs. There was so much he was tired of. With a final effort he struggled to stand, looking up through his window, smiling at the broad-faced moon. Percy reflected on his situation, wondering how best to measure the value of this journey. The things he had seen were beyond belief, taxing his spirit, perhaps more than he was willing to pay. Prison now seemed a reasonable alternative, a place he at least understood, not one beyond belief. Percy watched the pine trees swaying in the darkness, rooted in red clay, reaching up to the bright stars. Your heart decides what your head will believe, he decided. Perhaps the brightest and darkest lie next to each other in all of our souls. For the second time in recent memory Percy prayed, this time with a sincerity so direct and strong that it cut itself, like the facets of a diamond, into the deepest chambers of his heart. Then, Percy Brown lay on his bunk and fell into a deep, yet troubled, sleep.

The following afternoon, per his request, Percy Brown was escorted to the office of the chief psychiatrist, a short, elderly, balding Vietnamese man wearing thick, heavy-framed glasses topping a heavily scarred face. As Percy, in handcuffs and leg irons, entered the office, it occurred to him that in all his years in jails and prisons he had never met an American doctor. Percy sat in the hard plastic chair. The conditioned air felt barely cool and smelled stale. A lone window, covered by a heavy gauge grey steel wire screen, was tightly sealed against the dense rain silently sheeting down the glass. A low, leaden sky seemed to press its weight down upon the building itself. Across from Percy the doctor sat at his desk, ignoring him, reading a case file. It was very quiet except for the loud ticking of an unseen clock. The doctor’s pen scratched as he wrote in the file. Percy glanced around, unable to locate the clock. The doctor, Percy noted, was absently toying with a pair of shiny, stainless steel tweezers. The doctor looked up, staring at Percy as though surprised to find him there.

“I want to go back to the jail.”

“Oh?”

The ticking expanded to fill the small room. Percy looked around again, uncertain of words or thoughts. He knew he was sweating. Where was that damn clock, anyway?

“I . . . I can’t take this place anymore.”

“I see.” The doctor slowly twirled the needle-nosed tweezers while staring at Percy.

“Look,” Percy said, exhaling loudly, “I don’t belong here. I’m not crazy. Not at all. In fact, I’m just playing crazy, see? Playing. I fooled the doctor at the jail. I was just trying to beat my case.”

“Fooled the doctor?”

“Yeah.”

“Fooled Dr. Trung?”

“Yeah. I’m facing the third strike. Automatic life, you know? For a lousy box of Little Debbie snack cakes.”

“So, you fooled him, you think?”

Yeah, I think.” The clock ticked away. Percy wiped the sweat from his brow. His thigh muscle spasmed and the leg jumped involuntarily.

The doctor eyed him closely, then wrote something in his chart. “No need to beat your case now?”

“Man, I don’t care now.” Percy vigorously rubbed his eyes with both palms. The medication made his eyes itch and water. “I’ll go crazy if I stay here.”

“Go crazy?”

“Yeah.”

“Your medication will prevent that.”

“Shit. I don’t take that junk.”

“Oh?”

“That’s only for crazy guys.” Percy”s eyes itched terribly and he rubbed them again. “I just told you, I’m not crazy.”

“I see.” The doctor scribbled something else in the file. “Why do you believe you will go crazy here?”

“The shit I’ve seen here, it’s unbelievable. I’ve never seen shit like this, not even in jail or prison. This place is evil. Needs to be closed down, you ask me. Crazy shit.”

“Crazy?”

Percy arched his back suddenly, then shook out his cramping leg. He ached all over. He was very tired. Percy wanted out. Now. So, he told the doctor everything he had seen. Percy spoke of beatings and rapes, of nightsticks and cattle prods, and of runners amok. He told about suicides and castrations, of poor Benjamin and retarded Harold. He omitted nothing. He spoke of his friend, the moon, with its perfect understanding. He told how he had prayed, really prayed, until the gates of hell itself felt the ponderous stroke, prayed with a sincerity as certain as God’s promises to Abraham and his seed. He explained God’s promise that he was covered in mercies, a promise that now shone bright and perfect in its execution. And that, Percy explained, was why he could now return to the jail, shedding this fraud, this deception, like an old, ragged coat.

“And you believe all those things occurred here?”

“Sure. I saw them with my own eyes.”

The doctor stared, toying with the tweezers. “And tell me, Mr. Nelson, do you still believe that your name is,” the doctor glanced at the open file, “Percy Brown?”

“Yeah. It is. I told you last time, I had fake ID. Nelson is just an alias, to fool the police. ‘Course, it didn’t work. Fingerprints, you know?” Percy offered up his hands. “Since they booked me under Nelson, Nelson it is.”

“Fake?”

“Yeah.”

“To fool them?”

“Yeah.”

The clock continued ticking away, louder than ever. Percy squinted his eyes, blinking rapidly. His leg jumped again. Sweat slid down his cheek.

“I see.” The doctor scribbled more words, continuing to the next page.

“And your suicide attempt?” The doctor nodded at the long cut navigating across Percy’s neck like black railroad tracks.

“Fake.” Percy smiled weakly.

“Fake?”

“Yeah. Fake. Fake. Fake.” Percy waved his cuffed hands like a conductor, emphasizing each word.

“To fool us?”

“Yeah.”

“And last night, that was fake also?”

“Last night?”

“You dove off your sink.” The doctor idly tapped the tweezers against a coffee mug.

“No. No, I didn’t.”

“I have the report.”

“It’s a lie.”

“Both the nurse and the orderly witnessed it.”

“They’re lying. They just don’t like me.”

“Are they plotting against you?”

“Yeah, you can say that.”

“I see.” The doctor held the tweezers up, like a heron poised to spear an unsuspecting fish. “You may return to your cell, Mr. Nelson. Don’t worry, I will arrange everything.”

“That’s it? I’ll be going back to the jail?”

“I’ll arrange everything, do not worry.” The doctor smiled reassuringly.

“Thanks, doc. I’ll be glad to get out of here, I’ll tell you. Get visits. Cigarettes, canteen, telephone, recreation.” Percy stood up, elated.

“Yes, I’m sure. Goodbye now.” The doctor remained seated.

“Bye. Thanks again, Doc.”

Percy left the office, his leg chains tinkling and scraping the shiny, waxed floor. The doctor stared out the window, then swiveled in his chair, turning on a tape recorder. After a moment he spoke into the machine, twirling the tweezers absently.

“Patient is superficially persuasive, adept at faking sanity through innovative masking strategy of claiming he only feigns his psychosis. Diagnosis: patient is severely delusional with confirmed identity crisis, demonstrating psychotic thought process and exhibiting paranoid personality disorder. . . . Chronic suicidal tendencies noted. . . . Probable psychoactive substance dependence. . . . Prognosis: poor. Recommend petitioning court for six-month extension of commitment order for long-term treatment. . . . Increase dosages of current medications, institute regimen of Prolixin injections.”

THE END

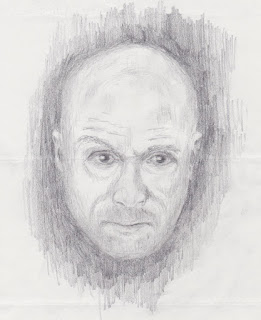

![]() |

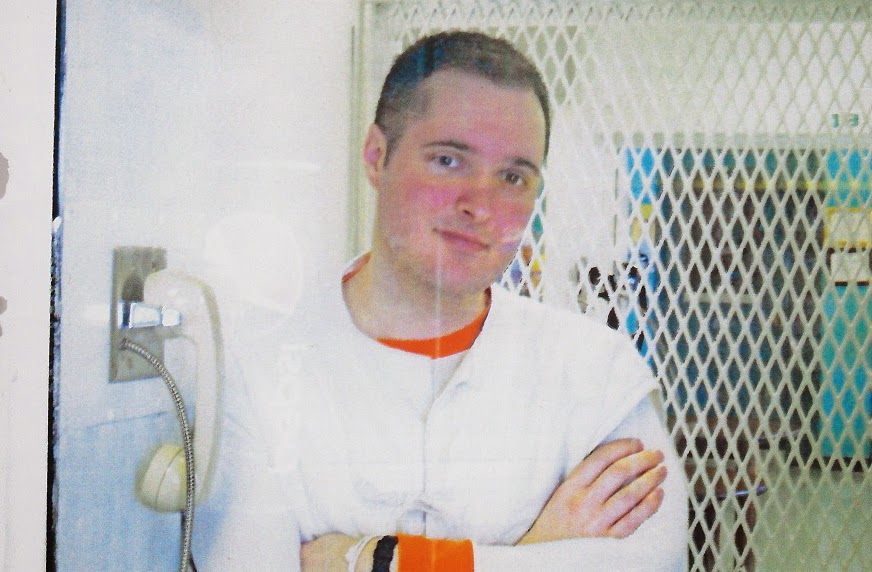

| William Van Poyck (pictured with his sister Lisa) |

Bill was executed by the State of Florida on June 12, 2013.

To read more of Bill's writing, visit http://www.deathrowdiary.blogspot.com

.jpg)