By Thomas Bartlett Whitaker

To read Chapter 18, click

hereThe genuine Rogelio Ramos, Jr., stayed in Cerralvo for five days. Every hour I spent with him increased my sense of unease, of some innate wrongness. All of his oily charisma was intact, as was his morbid self-absorption that bordered on amusing and his crude sense of humor. I tried to tell myself that something had changed in me since we had last seen one another, that the experiences of the last six months had altered my core to the point that I could simply no longer take Rudy without some help from Mr. Cuervo. This was undoubtedly true, but even after correcting for these shifts I found myself viewing him more and more as I would a very large, very ill-tempered and unmuzzled dog. As his stay lengthened, he began to ask more questions about my relationship with the Hammer, and it struck me by the second night that he was actually jealous of our rapport. If I had been less on my guard, I would have laughed at this, considering it wasn't so very long ago that I had thought it a real possibility that Gelo might make his existence substantially easier by simply shooting me in the face and dumping my body in the desert.

Fortunately Rudy cared more about getting coked up and chasing the local girls than in hanging out with me. I managed to keep the details of my employment secret from him, as well as my frequent trips to Monterrey. On the morning of his departure back to Texas, he got very serious, and claimed to "care deeply" for me. His concern seemed so counterfeit that I nearly laughed, but I managed to smooth my topography out before turning to face him.

"Oh? I really appreciate that, Rogelio. You've been very good to me. One day, when I am in a better position, I intend to make my appreciation keenly felt," I responded, dangling the lie-soaked carrot in front of his face. As far as I was concerned, I'd already paid him a ridiculous sum of money for taking me across the border, and we were more than even.

"You could do that now, if you wanted."

"Oh?" I asked, moderately amused that he was about to ask for more money. His coke habit must be getting really out of control, I remember thinking. My amusement was short-lived.

"Still got that Rolex? I always wanted one of those", he asked, his face filled with sudden interest.

Several things passed through my mind at once: "oh, so that's why he really came," followed swiftly by "is this a request or a threat?" which was in turn trailed rapidly followed by "no way am I giving him proof of life that he knows where I am." This last link in the chain kicked me into survival mode. I turned and looked right at him, and lied.

"Sorry, homes. I sold it during my first month down here. I had to eat, you know?" I was suddenly very glad that I had tucked my watch into a hidden pocket in my backpack after my arrival, and had hardly touched it since. This incident troubled me long after Rudy had departed. So much so that I brought it up to the Hammer the next time I saw him at the ranchita.

"And you theenk he want thees to use as proof of you whereabouts?" he asked me, occupied with a bunch of straps attached to a rather ornate saddle he had purchased that afternoon. I had expected him to respond with some species of keen interest to my concerns, but he appeared about as interested in his son's potential treasonous activities as Lord Byron was towards marriage counseling. Still, I thought about his question, trying to decide what I legitimately felt.

"Not really," I finally answered. "I think he wants it because he's a vain, tiny little man. But how would I know?"

"Look, Rudy—Conrad—whatever you name ees now. He would no send the poleece to Cerralvo, to the place where my family sleeps. Hees mother, she raise a fool, but she no raise a suicide." The way he said this so matter-of-factly gave me a small chill and I simply nodded and let the matter drop. Surely Gelo was right. I mean, he owned the chief of police, a fact that was not lost on the authentic Rudy. Surely he knew what would happen to him if he implicated his father in anything. I wasn't completely put at ease, but I decided I had little choice but to return to my life, such as it was, and hope that the son knew the father well enough to be terrified of him to the appropriate degree.

Work at the muebleria was as steady as always, though somewhat random. Don Hector was juggling so many projects at once that he seemed incapable of concentrating on any one of them for more than a few days at a time. Once we had gotten settled in, his ADHD would kick into overdrive and off we went, ping-ponging to another site. We were chasing Hector's ambitions, and, poor mortals that we were, it is not surprising that we never seemed to catch up with them or please him very much. The rest of the workers were accustomed to this electron-esque existence, and most of the non-skilled laborers talked a healthy amount of smack behind the patron's back. About the only two that didn't were the maestro and Adrian, Hector's master carpenter. Adrian was a man of few words, but he was a wizard on the lathe. I had no concept of this for the first few months of our acquaintance, as none of Hector's pending projects needed that sort of work done. I knew Adrian simply as my welding partner. I liked him very much, because he was so transparent. His likes and dislikes were simple, and so long as he worked hard and had his bucket of cold Carta Blancas at the end of the day, he was genuinely content.

If I never seemed to please the patron during work hours, I found the exact opposite to be the case once the day ended. The senora was tickled pink that I seemed to enjoy hanging out with Raul, and beyond elated that Cynthia and I played guitar together most nights. It's true that I genuinely liked both of Hector's two youngest children, that I found them far easier to talk to than pretty much anyone else in the country. They were smart and saw beyond the set ways of life in northeastern Mexico. What I couldn't seem to figure out was why Dona Maria seemed so intent on having me around. If she wasn't inviting me to dinner, she was pushing money into my hands to make sure Raul had enough on our trips to the big city. The biggest shock came one Friday night, when she thrust the keys to her gray Chevrolet Malibu at me and told me that it was too nice outside to sit upstairs and play such "dark music." Before I could quite figure out how it happened, I had been dragooned into service as Cynthia's chauffeur, driving her and three of her friends around town in the customary vuelta. I soon became the only sober person in the car, and, I add, probably the only sober person in any of the hundreds of vehicles engaged in this vast parade of hormones run amok. I don't think anyone paid us much mind, lost as we were in a sea of massive trucks, huge stereo systems blaring Norteno music, and gargantuan egos.

It isn't always easy to see how habits form, so subtle is the process. Playing guitar somehow morphed into more nights out, which slowly—in the minds of everyone but Cynthia, Raul, their friends, and myself—made us a pair of some sort. I wasn't really connected to the gossip stream of Cerralvo in any way, so the public's general error on this score was unknown to me until the Hammer began gloating over his "prophecy." It all seems very strange to me now when I look back on it; at the same time, at the beginning at least, there were absolutely no illusions held by myself, Cynthia, and her family. I was just an increasingly trusted worker and friend of the family. It was everyone else that had the wrong idea. Over the weeks that passed, I became increasingly convinced that Hector and the senora—especially the senora—wanted more to develop between me and their daughter. They certainly gave us plenty of privacy, to an extent that I found astonishing. I had known parents in Sugar Land who were so absorbed in the dramas of their solipsism that they failed to take notice of what their daughters were up to (and may the gods bless them for it). It was supposed to be different down here, considering how conservative Catholic Mexican parents are when it comes to their daughters. And yet they seemed to be practically begging me to despoil Cynthia, pushing car keys and money into my pocket every night, even going so far as to look the other way when Cynthia disappeared to Monterrey for the weekend. It was all very curious. I mean, I was still pretty messed up over my loss of Her, and so wasn't really in the mood for romance. That said, I happened to be cursed with a Y-chromosome, a fate compounded by the fact that of being twenty-four, and thus not exactly a frigging saint. I didn't exactly need or want the temptation, in other words.

Somehow, completely in the absence of any spoken contract, Cynthia and I fell into a sort of mercenary understanding. I hate to call it a relationship, because we seldom related. We simply both saw the forces at work here—though only she understood them in the beginning—and we both played them to our benefit. For reasons that I would soon discover, Cynthia had almost complete freedom assuming that I was reported to be involved, something she craved very deeply. I got a great deal of job security and a financial cushion that was hard to resist. I wish that I could tell you that I pondered long and hard over the ethics of this, but that would be a lie. Some inner homunculus disgustedly shook his head at me and marveled that one person could manage to get so tangled up in this many deceptions. I did feel some sense of shame, but I continued to justify my actions by claiming that I hadn't set this up, that I was just playing the cards that were dealt to me. I wasn't completely convinced, but this kept me in the game, kept me moving forward.

I definitely expected some sort of feedback from Raul, something very macho about treating-Cynthia-well-or-else. He said next to nothing, even after our trips to Monterrey continued as before, with Cynthia hanging out with her friends and me with mine. It was on one of these weekend forays in early December that the pieces fell into place for me. I wasn't feeling the ersatz sports bar that Raul had selected for the festivities that night, though I initially found the Mexican attempt at rendering a German bierhaus interesting. I left them there and walked back to San Nicolas rather than take the elevated train. Cynthia hadn't ridden to Monterrey with Raul and I, but I was not surprised to find her at the house when I returned, entourage in tow. The seven or eight girls at the shindig were pretty plastered by this point, and one of them bounded up to give me a big hug as I came through the front door. I had seen the girl before, but couldn't remember ever having heard her name. She was definitely one of the Monterrey gang, someone Cynthia had known from school. I was mostly mentally absent as I tried to extricate myself from her embrace, until she mentioned something about me being a "great fake boyfriend." Actually, the words she used were "novio contrahecho," or "counterfeit boyfriend." I was reflecting on how to respond to this when she left my side and returned to Cynthia on the couch. There was something intimate in the way they folded into each other, something more than the sum of body language. I don't know, a certain form of eye contact, a comfort in closeness that only comes from intimacy. Whatever the limbic cues, you can always tell when two people are in love, and I suddenly understood the whole charade in its entirety in a matter of seconds. Cynthia's eyes flicked from the girl and found mine, and I could see a well of concern blossom through the alcoholic haze. I merely smiled at her and mouthed "goodnight" before retiring to my room.

I felt like laughing at myself as I lay down to sleep, but I managed to control myself. I laid there thinking for a long time. About what it would be like to grow up gay, especially in a conservative backwater like Cerralvo. About how many lies someone would have to have told to one's father and mother, one's older brothers. About Cynthia's tiny but extremely close circle of friends in Cerralvo, and about how they always seemed to carry around a certain wariness towards everyone else, something that until now I had attributed to hauteur. I now understood why her parents were so interested in fostering some form of relationship between us, and why Raul hadn't seemed concerned about me doing anything dishonorable with his sister. Of course he would know; it struck me that this was why the two weren't closer, despite both of them needing the attention of someone not-Cerralvo. The parents most certainly didn't, I reasoned, but a certain suspicion had to lift its head above the bog of denial from time to time, and I must have seemed like the answer to their unconscious prayers. It was all so very sad. An index of all the ways we humans can hurt one another would surely require the felling of every last tree on the planet.

More immediate was the question of what I was going to do about the situation. I had grown up in a conservative household in a conservative suburb in a deeply red state. Gays were the Biggest Other imaginable, the living embodiment of all that was liberal and unholy. I had known people in high school that almost certainly were gay, but they weren't really on my radar. It wasn't until my last job that I had any close contact with any totally "out" homosexuals, and aside from a certain degree of latent wariness on my part, I came to like them very much. They were totally normal people with the same nobilities and flaws, the same dreams and fears as the rest of us, and aside from one minor difference in taste, not so different from myself. I've always been an outsider to this culture of ours, so I could sort of understand the distance they sometimes felt towards the rest of America. I wasn't really sure what would be required of me, but I decided it would cost me very little to guarantee some degree of freedom for Cynthia. I would do what I could. I didn't yet see the degree to which Cynthia's affection for me was tied to my compliance or how much bitterness would erupt once I had played my last role and exited stage left. All I saw at the time was that I had a chance to do something nice for someone, and that was a welcome change of pace. Sometimes you can do the right thing for the wrong reasons, and the wrong ones for the right ones, I reflected. I couldn't quite figure out which this was, and decided that it depended upon one's perspective. I went to sleep thinking about how odd "right" and "wrong" could be as concepts, when they blended so softly casual into one another, and, just before I drifted off, that at least I now knew exactly why Cynthia had punched Edgar when he had tried to steal a kiss from her.

The next morning I left a note for Raul saying that I would take the bus back to Cerralvo, and that I would see him again on Monday at work. As I was attaching this to the refrigerator with a magnet Cynthia hugged me from behind. It was the warmest thing she'd ever done to me, and I smiled at her as I turned around.

"You aren't mad?" she asked, still close enough that I could smell the lavender shampoo she used.

"No. But don't make me lie too much," I responded, tucking a wayward strand of hair behind her ear.

“It's just a little lie. And only because the truth would kill them. They will never understand, never, never, never. I wouldn't ask except I think you are good at telling them. Papi says your father has a lie where his heart ought to be."

That saying struck me (it sounds much better in Spanish)."That may be true, but don't put me on the spot," I said, stepping back. I wanted to tell her that there were no little lies, that they snowballed out of control before you knew it, but these are the sorts of truths that one has to learn by experience.

I left her in the glow of relationship security, probably the first time she had ever felt that. Not bad, I thought, for the fake son of a man with a pumping lie at his core. In this, perhaps I was more the Hammer's spiritual son than any of his actual biological progeny.

My mission for the day was to purchase a cell phone. I had decided that having one was worth the cost and the risk, as I seldom used it and limited the circle of those who knew of its existence. During the mid-aughts, none of the major carriers offered phones with contracts, so pay-as-you-go was the model. This was perfect for my needs: no names, no credit cards, just cash. I'd seen about a million Telcel vendors in the immense mercado downtown, so I figured I'd stop for a movie at the cinema and then make my way back to the market and then to the bus station. The only film showing in English with Spanish subtitles (the method I preferred for learning new vocabulary) was "The Chronicles of Riddick," a disappointing sequel with rather dubious translations; I recall thinking that it hadn't really taught me any new useful vocabulary. On the way to the subway I noticed something new: several shops with signs written not only in Spanish and English but also some sort of Asian script. I had never really considered that there might be an Asian community in Mexico, but clearly I was wrong to ignore the possibility because the small district I entered was packed with a Heinz 57 mix of Chinese (mostly Cantonese speakers, for some reason), Koreans, Vietnamese, and Cambodians. I had always enjoyed Houston's various Asian communities so, I ended up walking those avenues and alleyways for some time.

I ate a very passable meal of crab vermicelli and che pudding at a Vietnamese joint. As I was paying the tab I noticed a gray Audi S8 pull up to a seven or eight story brick building across the street. Three Asian men in suits climbed out quickly and the driver sped off. Two of the three gave the street an icy once-over while the third stubbed a cigarette out with his shoe and entered an unmarked yet garishly painted purple door. The two obvious goons followed on his heels. Everything about procession screamed that I had just witnessed someone near the high end of the food chain of the body economic. When you are running from the law, "dangerous underworld types" are transformed by the alchemy of desperation into potential allies, so I paused on leaving the restaurant to give the adjacent building a closer analysis.

I never saw the occupants of the gray Audi again, but in the alleyway between his building and the next I found a small storefront selling computer equipment, stereo gear, and cellular phones. The selection wasn't large but I wasn't in any position to be picky, and ended up with a nice little handset and 2500 minutes' worth of calling cards. Next door to this shop I came across what had to be the seediest internet cafe in all of Mexico. For starters, it was underground. Literally, I mean: you had to descend a dark, urine-smelling staircase before taking a hard left turn into the facility. I was met in a small atrium by a bored Asian of indeterminate origin who waved me towards a long room when I asked about the rates. I don't think he ever looked up from his comic book once, but I could be wrong. Inside the bunker—for that is what it was—I found two sixty or seventy foot rows, of fairly recent Dell, Acer, and Sony PCs, perhaps seventy-five in all (I would soon learn the exact count was 81). There were maybe a dozen people using these machines at this hour, and I selected one towards the rear of the hall. For some time I had been wanting to investigate what had been reported in the news about my disappearance, but I had been nervous that maybe the FBI had put some tracking software on the Chronicle's website that would alert them to anyone doing keyword searches about my case. Anyways, that is the reason I had been telling myself for months to explain why I wasn't investigating, but the truth is I was too much of a coward to witness potential photographs of the people I had left behind. I could barely stand to be myself at this point, and I felt that having to see the extent of the pain I had caused yet again would surely crack me. I was right—it was going to destroy me. I just didn't yet have the maturity to understand that such an atomization was the requisite first step towards rebirth in the human race. I sat there for a very long time, just staring at the blank screen, flicking through the various horrors that were available to me with the click of a few buttons.

Maybe it was the sinister ambiance of the place, but eventually the part of me that relishes taking risks overpowered the coward and I set about building the software suite that I would need to cloak my presence while I searched the web for traces of the missing Thomas Bartlett Whitaker. I downloaded a free IRC client and then trolled the warez channels, finally coming across nmap, the best port scanner I knew of. What nmap revealed about my workstation was a pretty sad indictment on whoever passed for a sysadmin around that place. I found four active trojans on the first scan, and about a gig of malware. If this Dell had been a patient in the hospital, about the only thing you could prescribe for it would be a bullet. I spent another two hours on warez until I found enough patches and antiviral software to make a go at disinfection. It took me about four hours total, but by the end of the afternoon I had seized root, cleaned out all of the malware and about 90% of the junk on the hard drive, partitioned the drive, and installed a Linux distro called KNOPPIX STD. This last came with a bewildering collection of tools for penetration testing, intrusion detection, vulnerability assessment, network monitoring, digital forensics, and password auditing: everything someone up to no good could ask for. I supplemented this with a few old tools I liked such as Metasploit and Snort. Before I left to return to Cerralvo, I gave the LAN a brief looksee and wasn't surprised at what I found: botnet zombies everywhere. The attack surface of the network was large, and apparently half the script kiddies in the city were taking advantage of the place. Old software, unpatched vulnerabilities, a firewall I could have penetrated with a plastic spork, and no Black Ice at all. I left that afternoon content that at least station number 39 was clean and would remain so until I returned sometime over the next few weeks.

I didn't return, not for a long time. That next week would trip the beginning of the end of my time in Cerralvo. I didn't see this end coming, of course; no one ever does.

While I had been enjoying the big city, yet another of the Hammer's many children returned to Cerralvo. Isabela lived in Roma, Texas, and worked as a secretary for a law firm. She was a few years older than I was, and rather pretty. She spoke some English but almost always spoke in Spanish. She had brought her two young sons to visit the family during the month of December, something which was fairly typical for many of the families in town. None of this gave me pause, save for the fact that the neat little teal house that graced the apex of la curva was hers. This meant that when I had chosen to symbolically move away from Gelo's ranch, I had literally moved in right next door to another of his places. He must have thought my choice of domicile hilarious, though he was wise enough not to mention this fact to me at the time. This also meant that all of the frigid showers I had been taking in the outhouse were unnecessary, because the teal house had a nice shower with a very large, very functional water heater Isabela seemed very tickled about this fact, and fortunately invited me to use her place whenever I wanted. This was right on time, because the temperatures had been declining rapidly during the month of November, and by the second week of December my showers had become...ah...rather quick, let's say.

I don't know what the Hammer had told her about me, but Isabela assumed from the beginning that I was actively working for her dad, claiming that "it had been years since he'd had an American on his payrool." She was actually a good source of intelligence on both Rogelios. She adored the father and abhorred the son, claiming the latter was an accident waiting to happen. I liked talking to Isabela because she was totally down for her father, even if she was not a part of his empire. She had grown up playing with killers and gun runners, and she legitimately didn't care what I was doing in Mexico. It became apparent over the first week of our chats that she knew I was no narco, and she came to the erroneous conclusion that this meant I had to be a pistolero of some sort. I knew this, and I did nothing to correct her, mostly because that was a better explanation than the truth. And, to be perfectly frank, because she was easy on the eyes and all immature men have some sort of atavistic desire to be perceived as dangerous to pretty women.

No unearned honor goes unpunished. The Friday of the week before Christmas was like any other: I woke, biked to work, slaved away under Don Hector's budding Ozymandias complex, and returned home to huddle under blankets and rest. I had just drifted off to sleep around 11pm when I heard banging on the front door of the taller, a pounding that instantly transmitted distress. Through the spyhole I saw Isabela, her body language radiating trouble.

"What's wrong?" I asked, after unlocking and opening the door. She poured inside, looking behind her anxiously.

"Some men, they follow me from the disco. The Spook, I know him from before."

I needed a minute to unpack this. Isabela's Spanish was normally very clear, but she had obviously downed a Margarita or seven at the discotheque and her words were a little slurred. On top of this, I'd never heard anyone with a nickname like "Spook" before and I was not confident enough with my capacities in the language to jump to quick conclusions.

"'Spook' is a nickname?" I asked, buying time, waking up.

"Si, his name is really Annibel. We...um...dated for a little while last year."

"Ah," I smiled, thinking Annibel was a girlish sort of name, not knowing it was the Spanish equivalent of Hannibal. I probably would have handled everything that came after a little differently had I known that, though maybe not. "And the boys?"

"Ben and Nicolas are spending the night at their abuelos. I wanted to have a little me time, but this bastard, he won't leave me alone, so I leave. And now he is here, following me."

I'd always loved the way English terms like "me-time" got co-opted by the people of northern Mexico, and, stupid as it sounds, it was my pleasure at finally having arrived at a place where I could actually understand most of the people around me that propelled me into action. I could call it chivalry and give it a fancy title, and maybe there was a little bit of that. I know we the condemned aren't supposed to possess any of the cardinal virtues, but even in my darkest of days I would open a door or an umbrella for a woman. You can make of that what you will. As I think back on that night, however, I am increasingly convinced that what really motivated me more than anything else was a sort of desire for annihilation, Freud's todtriebe on steroids. It isn't so much an active suicidal impulse; it's more subtle than that, something numb and warm and hollow, a sense of the emptiness of things, a shadow behind the shadows, a sense that things are already about as messed up as they can get, so you might as well just go ahead and see how the whole business can be tipped over the edge and finished with. There is almost an absurd sort of humor to it, Meursalt's laughter at the priest echoing down the decades and over the ocean to ring quietly in your head.

Of course, things went bad almost from the first second. Isabela had mentioned dating this Spook, but she had neglected to tell me that he was still very much in love with her. She had also omitted the fact that when this Lothario had decided to follow her home, he did so with eight of his friends in three trucks. There wasn't a lot of time to ponder these revelations on my part. Nor do I think I would have retreated back into the taller had I a few ticks to evaluate my position. There's something about fighting that is very pure, very binary. You hit, or you get hit. You rearrange the other guy's face, or he does yours. There's no ambiguity here, no dithering over minutiae, none of the indeterminacy of our postmodern era. A brief, shouted "Quien es ese tipo?" and then a clumsy drunken roundhouse aimed right at your pearly whites. You parry, spin, put your foot into his balls; only people who have never been in a fight think that there are rules for "fairness." No time to think about this, because then red-hat is on you and he's faster or less drunk than Spook and you can't put him down quite fast enough before the rest of the throng arrives and then it doesn't really matter how fast or strong you are because this isn't Hollywood and no one beats up nine dudes in a fight no matter how long they've been drinking. You manage to get some hits in and feel some tiny whisper of satisfaction at the pop goatee-boy's elbow makes when you snap it before the big fucker with the Texans jersey rams his pistol into your forehead two or three times and then the lights go out hard. So totally, in fact, that you don't feel a thing when they kick in three of your ribs. It's a measure of just how far gone you are that even after the x-rays, the stitches, and the headaches, even after you wake up minutes or millennia later on the cold dirt, all you can think to do is spit some blood out on the vampire earth and start to laugh. How you wouldn't have changed a thing.

That's how Isabel found me, however long later. I don't really know what happened to her during the fight, save that she somehow managed to get into her house. After the pack had had its fun it had departed, probably because some of them were sober enough to have started thinking about just how limited their life expectancy might be if Isabela decided to give her padre a ring.

That's actually the thing my rapidly gyrating mind focused on as a lighthouse, guiding me back to the world of color and pain. I knew exactly what the Hammer would do once he found out about this. Even the honor of a fake son had to be avenged, and for some reason I felt overwhelmed by the need to ensure that nothing happened to Spook et al. Later, when they set my ribs, I admit to a few errant moments when I wished otherwise, but what my concussed mind latched onto in those first hours was that this just stop, that I had wanted this and needed it, and that blame and consequences were pointless. There's no such thing as justice in the jungle, and I didn't understand why anyone would want otherwise.

I cannot describe the next twelve or so hours clearly. I know what happened mostly from what other people told me afterwards. This is supplemented by some memories of my own, though I know my brain wasn't in a good state and these must be viewed skeptically. I know I made Isabela promise not to call her father, a promise she broke almost immediately. I know I borrowed the keys to her Ford Contour, and went looking for Spook with the ax handle I lifted from Emilio's workshop. My plan, I think, was to somehow locate Spook, get him alone, introduce him to the wonderful density and feel of white ash, and while he was still mewling and insensate at my feet call the Hammer and show him that I got my own vengeance and he could just let it go. It seemed a wonderful plan.

Of course it didn't work. I did find the collection of trucks that I had seen for a brief few seconds before things got kinetic outside of a local cantina. I even found a lovely and conveniently placed shrub to hide behind near the cantina. That's where el Mochaorejas and Abelardo found me, some unknown amount of time later, talking to myself (or the shrub) and nearly frozen solid. I do remember taking a swing at the Ear Chopper, and I do not believe the speed at which he ducked and seized the ax handle from me is a false memory. The man was a tub of lard but he was a damned fast tub of lard. I vaguely recall the trip to the hospital, and any doubts about the veracity of this memory were eliminated when I woke up the next day. My body was wrapped in gauze and my brain was wrapped in oxycontin, lovely oxycontin, thanks to the bottle I found next to my bed. The little sticker listed one of my many fake names, and I started to laugh at this until my chest gave me about a million reasons not to. The rest of the events of the night before, I got from Isabela, when she came by to check on me. She wouldn't give me a straight answer about what Gelo had done to my attackers, save to say that neither of us would be seeing Spook again. She seemed oddly put out by me. I wasn't expecting her to swoon and hover over me all Florence Nightingale fashion, but considering she'd basically gotten my ass kicked I expected something other than barely concealed incivility. I don't know, maybe she expected me to Bruce Lee the whole hoard or something. Maybe she still liked the bastard. Either way, she clearly felt I had failed her in some way, and after several uncomfortable visits I told her I was fine and just wanted to be alone. For the first time since the fight, she seemed pleased.

The Hammer eventually came around later that week. I had called in sick to work, figuring that an inability to walk straight might prevent me from laying block in an orderly manner. My left eye was a brilliant red, which contrasted nicely with the purple bruises which were encircling it. There were shades of greenish-blue on my ribs that were new to science, and I was feeling these and my ribcage when Gelo banged on the door. I hobbled over and threw it open. For about a nanosecond his face was completely unguarded, and I gave his micro-expression of shock and pity a wicked grin. I mean, I hadn't lost any teeth in the fracas, which was something of a small miracle.

"You are looking well," he recovered quickly.

"You have a heart made of lies."

"Okay, you ees looking like you play a game of cheeken with a Lincoln. On foot."

"Better," I turned, walking back inside.

"I have water and more water," I told him. "If that isn't exciting enough for you, I can spike it with some of these primo opiates. They're pretty grand."

"Maybe next time, when you—"

"What did you do with them, Gelo?" I interrupted my back still to him.

"They no come back. Thees I promise."

"What does that mean? My brain is swollen, and not in the good way. Be more precise. Did you kill them?"

He moved around the taller, slowly inspecting Emilio's workshop, which, as always, was strewn with speakers in various stages of repair. He took his time.

"I explain to them that thees town is off limits. They come here to visit the family, to flash the American money and have fun weeth the girls. But they always go back to work. Now, they will stay there. Because if they come back, it will be the last theeng they do. I speak to the families, and we are all...how you say, estamos de acuerdo with all thees. They is very appreciative."

I breathed a deep sigh of relief and then wished I hadn't. What a fucked up place, I thought, when a family has to thank the man who decided not to kill their son.

"Ah, the ax," Gelo exclaimed. He had found the handle and had removed it from its peg. "The famous ax. The Mochaorejas, he like thees part of the story very much, you waiting in the bushes to attack nine peoples. He say you ees crazy in the best way."

"Thanks. I'll think of something witty to say to that in a few weeks."

He replaced the handle and turned to look at me for some time. He used to make me very nervous when he did this. By now I understood that this was just his way, and any cat-staring-at-a-mouse feeling that came over you was all in your head.

"There ees a problem."

"I thought they wouldn't be back," I replied, not for the first time noting how his confidence always seemed to be wrapped in a heavy layer of uncertainty.

"Not weeth thees payasos. No, con Rudy." This caused me to go on alert, and the spinning in my head accelerated. "You remember he leave always to go to party? To be with some woman? Isabela, she knows thees girl, runs into her in town. They get to talking, talking about heem, how great he ees, all of these mierda. Isabela, she plays along. Thees puta, she theenk Rudy love her, ees talking about taking her to los Estados Unidns."

"Telling her how?"

"Exacto. They talk on the phone, several time each week."

"Okay," I stalled, thinking this through.

"Rudy, he has no loyalty. And thees girl, she is no very beauty. You see?"

"He's using her for intel."

"Yes, maybe. Who can say? But I get the feeling, and these feeling I always trust. It ees time you go on a leetle vacation. A chance to heal thees wreck of a face and for heem to lose you."

"I'll go to Monterrey."

"No. If he is move against you, he is move against me tambien I have already report this to...people. They want you moved to someplace else, so we do thees my way."

"Okay. What is your way?”

"I have many places for the hiding."

Of course he did.

"Any one in particular?" I asked, legitimately curious.

"Si. One in the mountains. Ess very nice. Very preety, like a photograph. You leave tonight. In two hour. I already speak to Don Hector. I tell heem I need you for construction project for two month, since you is so handy," he said, smiling. I could tell he enjoyed removing me, a sort of checkmate to Hector's obvious pleasure in bossing around one of his kids.

"Two months? I can do two months," I murmured, mostly to myself.

"Maybe more. We will see how theengs is in Marzo. Thees place, eet is a leetle out of the way. You will like. It ees very cold place." This last sounded strange to me, but I let it go.

I remembered his description of the place for every last second of my time on the mountain. Every single freezing moment. I repeated them often to myself as I sent my ax into frozen ironwood "You weel love eet, ees very nice, very preety." It became a sort of mantra. Not even god could have found me on that mountain, so lost was I to the world. It took Abelardo the better part of a night and a morning driving down backroads to arrive at the place, a 500 square foot concrete shack surrounded by oak trees. The Hammer was right about one thing, though: it was cold. The kind of cold that gets in deep inside of your bones, slows everything down to the point that the world appears motionless. The kind of cold that becomes you, redefines you. The kind of cold that makes you a part of it.

To be continued....

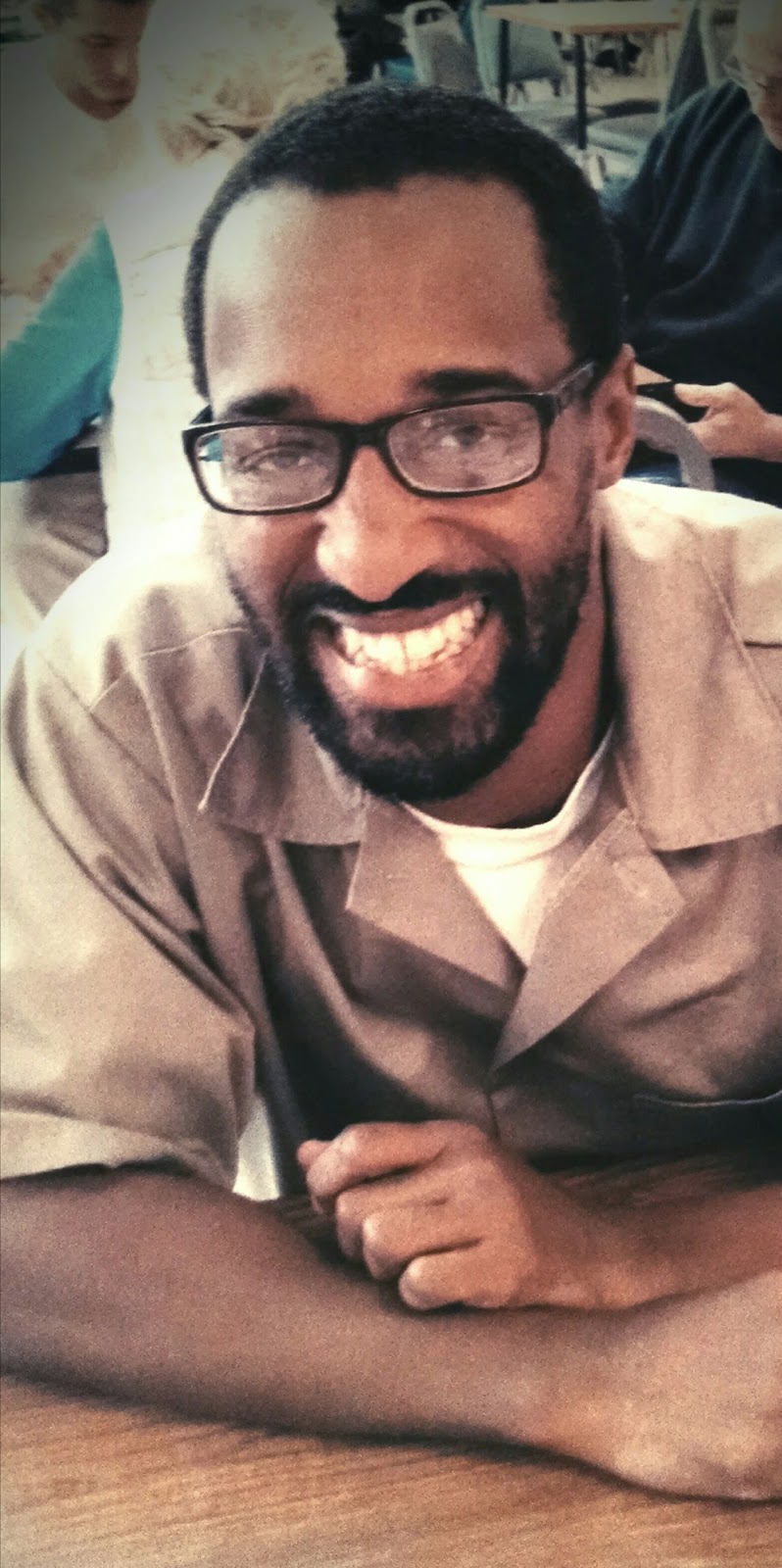

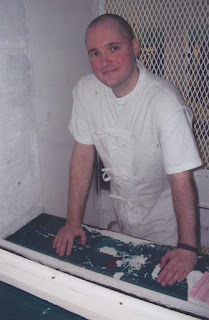

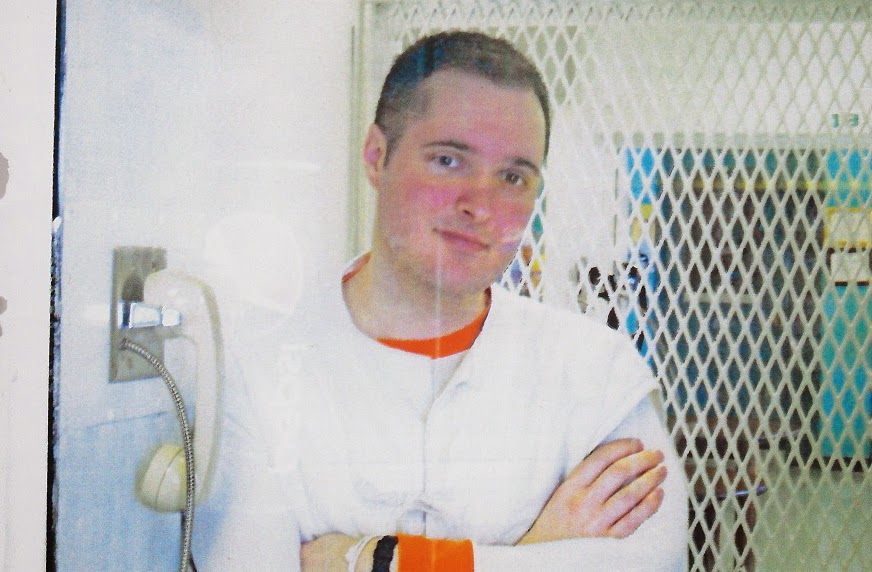

![]() |

Thomas Whitaker 999522

Polunsky Unit

3872 FM 350 South

Livingston, TX 77351 |

.jpg)